‘Running isn’t everything’: Villanova track HC Marcus O’Sullivan on difficult adjustment from athlete to coach

VILLANOVA, Pa. (BVM) — Villanova men’s track and field and cross country head coach Marcus O’Sullivan took one 12-mile walk each Sunday with his dad in Ireland where he grew up. Around seven, eight or nine years old — he can’t quite remember — plodding alongside his dad, he turned and asked if he could one day make the Olympic team. At that point, he had never ran competitively. The biggest thing that he ever wanted was to win a wheelbarrow race with his friend, Greg Ford.

“[He said] 1976 is coming up soon in Montreal and 1980 is already going to be in Moscow and I think that will be too early for you,” O’Sullivan said of his father. “But 1984 is a good year.”

O’Sullivan describes the 1984 Olympics, the first of his four Olympic appearances, as a “utopia of bliss” and a “big party full of athleticism.” Casual security, the Beach Boys playing on the lawn and there were soda fountains everywhere.

“It was like ‘Willy Wonka and the Chocolate Factory’ and I had the golden ticket,” O’Sullivan said. “But after that, the Olympics became more professional. There was something special about Los Angeles that year.”

In his career, O’Sullivan set an indoor record for the 1500-meter with a time of 3:35:40, won the Wanamaker Mile in the Millrose Games in Madison Square Garden six times and became one of only three men in the world to run a sub four-minute mile over 100 times.

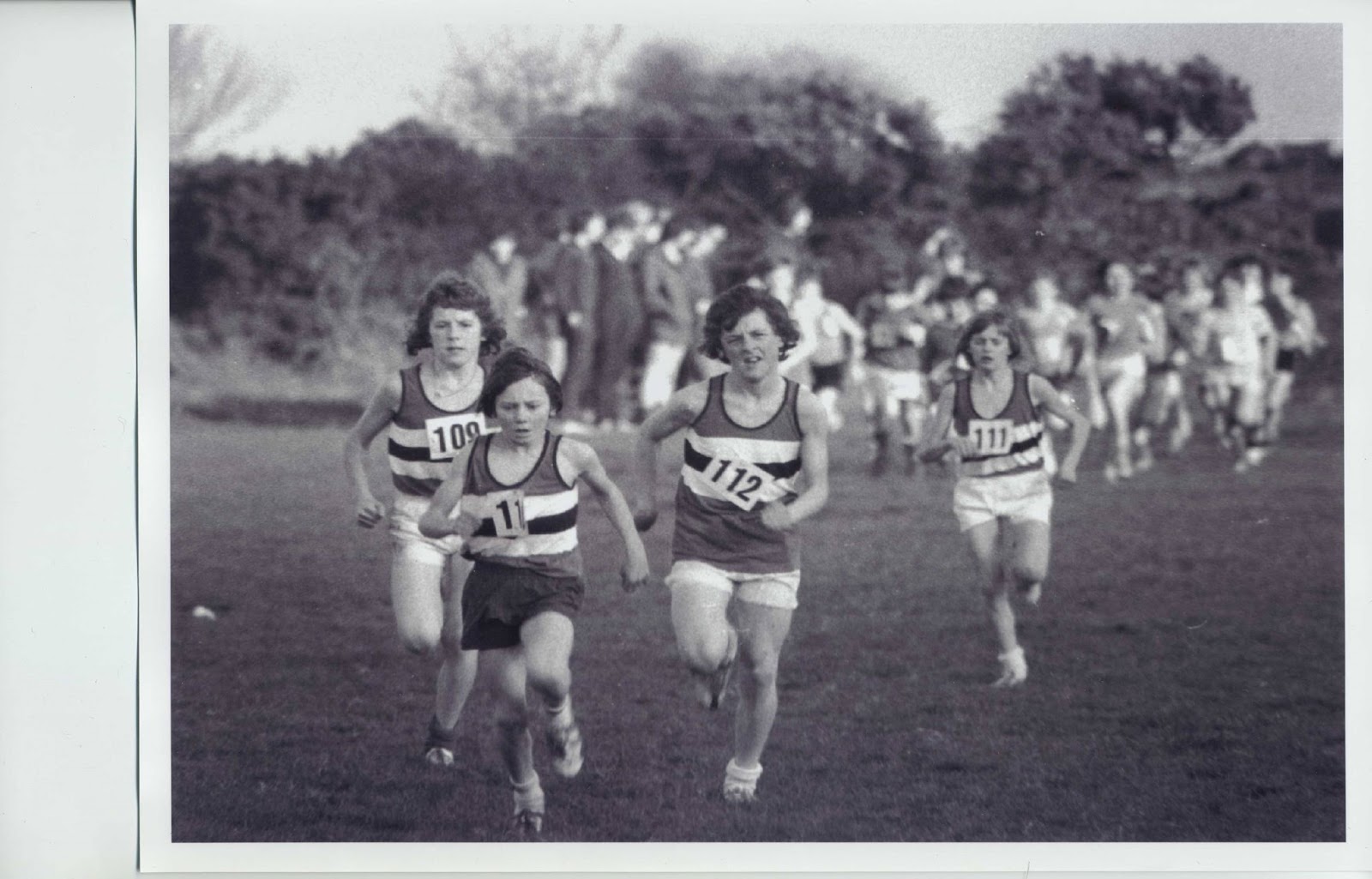

Neither O’Sullivan nor his father had to mention the Olympics again. He said that the seed had been planted in his mind at that moment as a kid in Ireland. He went to a local club and lost every race to a group of girls. Dejected, he went back and quit. In middle school, he was told that he was too small for the team. In high school, he made the team, but was not the best. He never won a field day and certainly was not good enough to earn a scholarship.

“I was a late bloomer,” O’Sullivan said. “That is one of the reasons that I think my career went so long.”

He got a job working on sailboats during the day. Legendary runner Steve Prefontaine offered to train him by night and helped him earn a scholarship to Villanova, where he became a two-time NCAA champion, was a part of six Penn Relays titles and won 10 Big East crowns.

When the time came to return to Villanova as a head coach, he did not know how to turn it down. Coming off of a great career, his background was in business and he was planning to work on Wall Street. He felt a certain obligation to Nova because it was family.

“My first year of coaching was the lowest and most miserable I had ever been,” O’Sullivan said. “I was miserable because, as an athlete, you are self-centered. Coaching is more about giving than taking and I was flabbergasted and frustrated that people needed so much.”

O’Sullivan is constantly reminded of how self-centered someone can be as an athlete. The focus on self-improvement and the packed stadiums all made him focus inward. His favorite moment as a runner also comes with the shame of recognizing his own selfishness. In 1986, he was encouraged to return home to Ireland to attempt a 4×1 mile world record as a part of the Live Aid fundraisers. He did not want to do it. When he arrived at an empty stadium, he was annoyed. When he came back from warm-ups though, the stadium was packed with kids, boxers and families. O’Sullivan and his team broke the world record that day. Stands and buckets around the stadium collected $40,000 for the Ethiopian famine.

“Sometimes you don’t realize the rhyme or reason until decades later,” O’Sullivan said. “I still have the photo on my wall of Ethiopia that was given to me that day. Thirty years later I recruited a kid from Ethiopia. I was so shamefully self-centered at the time that I couldn’t see.”

Two years in, O’Sullivan was still miserable in his new position as a coach, struggling to focus outward on his athletes, keep up with the emotional grind of coaching and with the ability to accept that not all of his athletes are as intensely driven as he was.

His daughter, running at Nova at the time, said, “Dad, you need to calm down and realize that not everyone has the same expectations for themselves, drive and determination and that’s OK.”

There is one moment that O’Sullivan attributes to finding peace in coaching. After one of his runners lost his mom, O’Sullivan helped organize a group of cars to get the team to Norristown, Pa., for her funeral. That is the day his whole view of coaching changed.

“When I saw the other kids supporting him, it felt good to be a part of the support,” he said. “I felt a huge change. On that day, I realized that I could buy into trying to make life better for others. By year three I was hooked on the idea that coaching isn’t about the X’s and O’s but about helping, mentoring and being a positive source for these kids.”

There is still a grind in giving so much emotion to the players and he describes it as a “chronic grind of emotional drain.” Behind the glamour of track and field is so much that the spectator never sees.

He says that emotional grind is the huge difference between running and coaching — very different, but very enjoyable.

But O’Sullivan’s wife would tell him that “he was physically home, but emotionally he was not.”

In his 23rd year as Villanova’s head coach, O’Sullivan aims to coach for self improvement and for the person, not the athlete.

“It took me a long time to learn that being pushed to the highest athletic level is not what everyone needs,” O’Sullivan said. “I learned not to define kids on my team just by their athletics. Running isn’t everything.”

Two of his past runners were two Fulbright scholars: a writer for “Saturday Night Live” and a screenwriter in Los Angeles. He has coached 15 national champions, 103 All-Americans, 203 Big East champions, multiple Capital One Academic All-Americans, scholar athletes and his own two children.

He would not want to coach anywhere else. By being back at Villanova, this time with perspective, O’Sullivan says that he gets to appreciate the community that makes up the school through his kids more than he could himself when he was a student.

“I came because I wanted to be back at Villanova, not necessarily because I wanted to coach,” O’Sullivan said. “But I have no regrets now.”